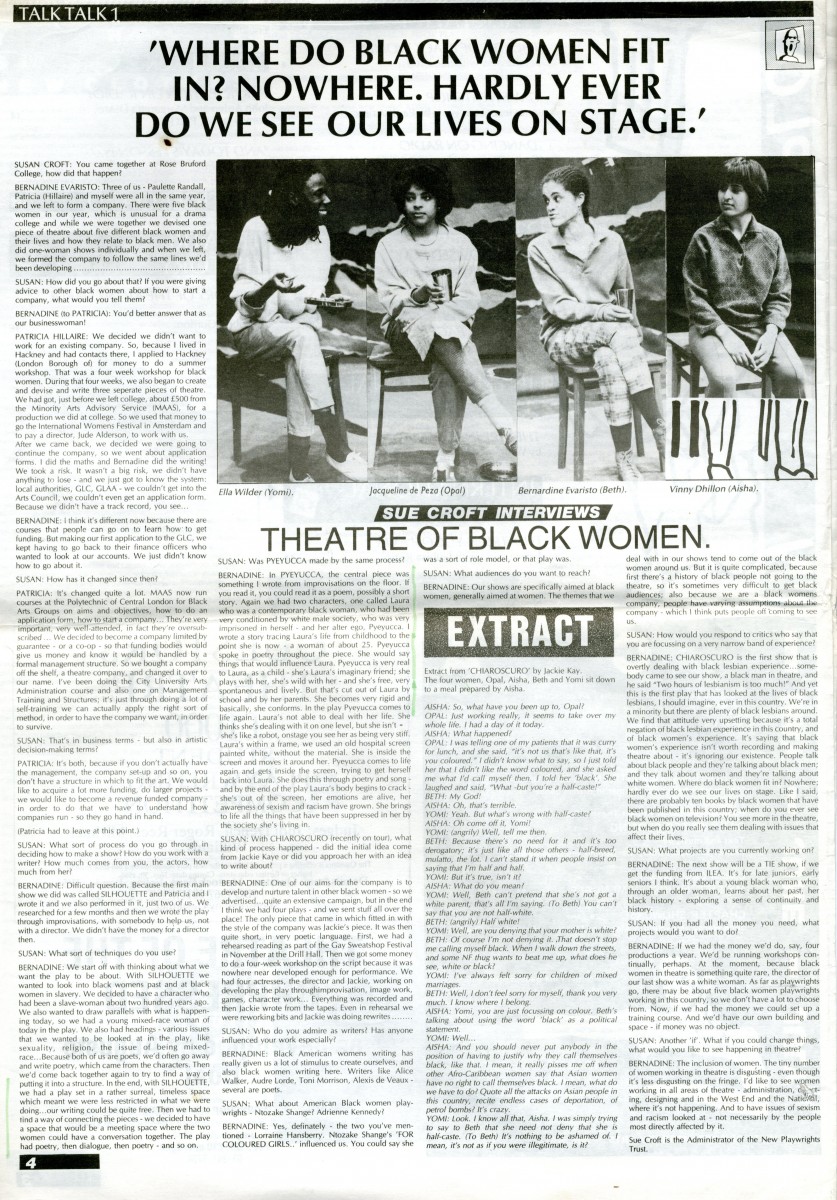

Cast of Chiaroscuro, pictured above: Ella Wilder (Yomi). Jacqueline de Peza (Opal) Bernardine Evaristo (Beth). Vinny Dhillon (Aisha).

Transcript of article

SUSAN CROFT: You came together at Rose Bruford College, how did that happen?

BERNADINE EVARISTO: Three of us – Paulette Randall,Patricia (Hilaire) and myself were all in the same year, and we left to form a company. There were five black women in our year, which is unusual for a drama college and while we were together we devised one piece of theatre about five different black women and their lives and how they relate to black men. We also did one-woman shows individually and when we left, we formed the company to follow the same lines we’d been developing.

SUSAN: How did you go about that? If you were giving advice to other black women about how to start a company, what would you tell them?

BERNADINE (to PATRICIA): You’d better answer that as our businesswoman!

PATRICIA HILAIRE: We decided we didn’t want to work for an existing company. So, because I lived in Hackney and had contacts there, I applied to Hackney (London Borough of) for money to do a summer workshop. That was a four week workshop for black women. During that four weeks, we also began to create and devise and write three separate pieces of theatre. We had got, just before we left college, about £500 from the Minority Arts Advisory Service (MAAS), for a production we did at college. So we used that money to go the International Women’s Festival in Amsterdam and to pay a director, Jude Alderson, to work with us. After we came back, we decided we were going to continue the company, so we went about application forms. I did the maths and Bernadine did the writing!

We took a risk. It wasn’t a big risk, we didn’t have anything to lose – and we just got to know the system: local authorities, GLC, GLAA – we couldn’t get into the Arts Council, we couldn’t even get an application form. Because we didn’t have a track record, you see.

BERNADINE: I think it’s different now because there are courses that people can go on to learn how· to get funding. But making our first application to the GLC, we kept having to go back to their finance officers who wanted to look at our accounts. We just didn’t know how to go about it.

SUSAN: How has it changed since then?

PATRICIA: It’s changed quite a lot. MAAS now run courses at the Polytechnic of Central London for Black Arts Groups on aims and objectives, how to do an application form, how to start a company… They’re very important, very well-attended, in fact they’re oversubscribed.. We decided to become company limited by guarantee – or a co-op – so that funding bodies would give us money and know it would be handled by a formal management structure. So we bought a company off the shelf, a theatre company, and changed it over to our name. I’ve been doing the City University Arts Administration course and also one on Management Training and Structures; it’s just through doing a lot of self-training we can actually apply the right sort of method, in order to have the company we want, in order to survive.

SUSAN: That’s in business terms – but also in artistic decision-making terms?

PATRICIA: It’s both, because if you don’t actually have the management, the company set-up and so on, you don’t have a structure in which to fit the art. We would like to acquire a lot more funding, do larger projects – we would like to become a revenue funded company – in order to do that we have to understand how companies run – so they go hand in hand.

(Patricia had to leave at this point.)

SUSAN: What sort of process do you go through in deciding how to make a show? How do you work with a writer? How much comes from you, the actors, how much from her?

BERNADINE: Difficult question. Because the first main show we did was called SILHOUETTE and Patricia and I wrote it and we also performed in it, just two of us. We researched for a few months and then we wrote the play through improvisations, with somebody to help us, not with a director. We didn’t have the money for a director then.

SUSAN: What sort of techniques do you use?

BERNADINE: We start off with thinking about what we want the play to be about. With SILHOUETTE we wanted to look into black women’s past and at black women in slavery. We decided to have a character who had been a slave-woman about two hundred years ago. We also wanted to draw parallels with what is happening today, so we had a young mixed-race woman of today in the play. We also had headings – various issues that we wanted to be looked at in the play, like sexuality, religion, the issue of being mixed race… Because both of us are poets, we’d often go away and write poetry, which came from the characters. Then we’d come back together again to try to find a way of putting it into a structure. In the end, with SILHOUETTE, we had a play set in a rather surreal, timeless space which meant we were less restricted in what we were doing… our writing could be quite free. Then we had to find a way of connecting the pieces – we decided to have a space that would be a meeting space where the two women could have a conversation together. The play had poetry, then dialogue, then poetry – and so on.

SUSAN: Was PYEYUCCA made by the same process?

BERNADINE: In PYEYUCCA, the central piece was something I wrote from improvisations on the floor. If you read it, you could read it as a poem, possibly a short story. Again we had two characters, one called Laura who was a contemporary black woman, who had been very conditioned by white male society, who was very imprisoned in herself and her alter ego, Pyeyucca. I wrote a story tracing Laura’s life from childhood to the point she is now – a woman of about 25. Pyeyucca spoke in poetry throughout the piece. She would say things that would influence Laura. Pyeyucca is very real to Laura, as a child – she’s Laura’s imaginary friend; she plays with her, she’s wild with her – and she’s free, very spontaneous and lively. But that’s cut out of Laura by school and by her parents. She becomes very rigid and basically, she conforms. In the play Pyeyucca comes to life again. Laura’s not able to deal with her life. She thinks she’s dealing with it on one level, but he isn’t – she’s like a robot, onstage you see her as being very stiff. Laura’s within a frame, we used an old hospital screen painted white, without the material. She is inside the screen and moves it around her. Pyeyucca comes to life again and get inside the screen, trying to get herself back into Laura. She does this through poetry and song – and by the end of the play her awareness of sexism and racism have grown. She brings to Iife all the things that have been suppressed in her by the society she’s living in.

SUSAN: With CHIAROSCURO (recently on tour), what kind of process happened – did the initial idea come from Jackie Kay or did you approach her with an idea to write about?

BERNADINE: One of our aims for the company is to develop and nurture talent in other black women – so we advertised … quite an extensive campaign, but in the end I think we had four plays – and we sent stuff all over the place! The only piece that came in which fitted in with the style of the company was Jackie’s piece. It was then quite short, in very poetic language. First, we had a rehearsed reading as part of the Gay Sweatshop Festival in November at the Drill Hall. Then we got some money to do a four-week workshop on the script because it was nowhere near developed enough for performance. We had four actresses, the director and Jackie, working on developing the play through improvisation, image work, games, character work … Everything was recorded and then Jackie wrote from the tapes. Even in rehearsal we were reworking bits and Jackie was doing rewrites….

SUSAN: Who do you admire as writers? Has anyone influenced your work especially?

BERNADINE: Black American women’s writing has really given us a lot of stimulus to create ourselves, and also black women writing here. Writers like Alice Walker, Audre Lorde, Toni Morrison, Alexis de Veaux – severaI are poets.

SUSAN: What about American Black women playwrights – Ntozake Shange? Adrienne Kennedy?

BERNADINE: Yes, definitely – the two you’ve mentioned – Lorraine Hansberry. Ntozake Shange’s ‘FOR COLOURED GIRLS’ influenced us. You could say she was a sort of role model, or that play was.

SUSAN: What audiences do you want to reach?

BERNADINE: Our shows are specifically aimed at black women, generally aimed at women. The themes that we deal within our shows tend to come out of the black women around us. But it is quite complicated, because first there’s a history of black people not going to the theatre, so it’s sometimes very difficult to get black audiences; also because we are a black women’s company, people have varying assumptions about the company – which I think puts people off coming to see us.

SUSAN: How would you respond to critics who say that you are focussing on a very narrow band of experience?

BERNADINE: CHIAROSCURO is the first show that is overtly dealing with black lesbian experience… somebody came to see our show, a black man in theatre, and he said: “Two hours of lesbianism is too much!” And yet this is the first play that has looked at the lives of black lesbians, I should imagine, ever in this country. We’re in a minority but there are plenty of black lesbians around. We find that attitude very upsetting because it’s a total negation of black lesbian experience in this country, and of black women’s experience. It’s saying that black women’s experience isn’t worth recording and making theatre about – it’s ignoring our existence. People talk about black people and they’ re talking about black men; and they talk about women and they’re talking about white women. Where do black women fit in? Nowhere; hardly ever do we see our lives on stage. Like I said, there are probably ten books by black women that have been published in this country; when do you ever see black women on television? You see more in the theatre, but when do you really see them dealing with issues that affect their lives.

SUSAN: What projects are you currently working on?

BERNADINE: The next show will be a TIE show, if we get the funding from ILEA. It’s for late juniors, early seniors I think. It’s about a young black woman who, through an older woman, learns about her past, her black history – exploring a sense of continuity and history.

SUSAN: If you had all the money you need, what projects would you want to do?

BERNADINE: If we had the money we’d do, say, four productions a year. We’d be running workshops continually, perhaps. At the moment, because black women in theatre is something quite rare, the director of our last show was a white woman. As far as playwrights go, there may be about five black women playwrights working in this country, so we don’t have a lot to choose from.

Now, if we had the money we could set up a training course. And we’d have our own building and space – if money was no object.

SUSAN: Another ‘ if’. What if you could change things, what would you like to see happening in theatre?

BERNADIN E: The inclusion of women. The tiny number of women working in theatre is disgusting – even though it’s less disgusting on the fringe. I’d like to see women working in all areas of theatre – administration, directing, designing and in the West End and the National, where it’s not happening. And to have issues of sexism and racism looked at – not necessarily by the people most directly affected by it.

Sue Croft is the Administrator of the New Playwrights Trust.

Extract from ‘CHIAROSCURO’ by Jackie Kay.

The four women, Opal, Aisha, Beth and Yomi sit down to a meal prepared by Aisha.

AISHA: So, what have you been up to, Opal?

OPAL: Just working really, ii seems to take over my whole life. I had a day of it today.

AISHA: What happened?

OPAL: I was telling one of my patients that it was curry for lunch, and she said, •it’s not us that’s like that, it’s you coloured.” I didn’t know what to say, so I just told her that I didn’t like the word coloured, and she asked me what I’d call myself then. I told her ‘black’. She laughed and said, “What -but you’re a half-caste!”

BETH: My God!

AISHA: Oh that ‘s terrible.

YOMI: Yeah. But what’s wrong with half-caste?

AISHA: Oh come off it, Yomi!

YOMI: (angrily) Well, tell me then.

BETH: Because there’s no need for it and it’s too derogatory; it’s just like all those others – half-breed, mulatto, the lot. I can’t stand it when people insist on saying that I’m half and half.

YOMI: But it’s true, isn’t it?

AISHA: What do you mean?

YOMI: Well, Beth can’t pretend that she’s not got a white parent, that’s all I’m saying. (To Beth) You can’t say that you are not half-white.

BETH: (angrily) Half white!

YOMI: Well, are you denying that your mother is white?

BETH: Of course I’m not denying it. That doesn’t stop me calling myself black. When I walk down the streets, and some NF thug wants to beat me up, what does he see, white or black?

YOMI: I’ve always felt sorry for children of mixed marriages.

BETH: Well, I don’t feel sorry for myself, thank you very much. I know where I belong.

AISHA: Yomi, you are just focussing on colour. Beth’s talking about using the word ‘black’ as a political statement.

YOMI: Well …

AISHA: And you should never put anybody in the position of having to justify why they call themselves black, like that. I mean, it really pisses me off when other Afro-Caribbean women say that Asian women have no right to call themselves black. I mean, what do we have to do? Quote all the attacks on Asian people in this country, recite endless cases of deportation, of petrol bombs? It’s crazy.

YOMI: Look. I know all that, Aisha. I was simply trying to say to Beth that she need not deny that she is half-caste. (To Beth) It’s nothing to be ashamed of. I mean, it’s not as if you were illegitimate, is it?